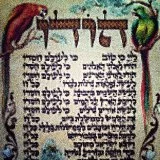

One of the high points of the Passover Seder every year, especially when our kids were growing up, came toward the end, when we’d recite the Great Hallel, Psalm 136.

We did this responsively, with the reader calling out the first line, “Give thanks to Hashem, for He is good!” and everyone responding, “For His love endures forever!” and then on through all twenty-six verses. As our kids got older, we switched to the Hebrew for the response line: Ki l’olam chasdo!

As always, the original language enriches our understanding of the text. Chasdo is the masculine singular possessive of chesed, our middah for the week, which we translate as “lovingkindness,” or in various Haggadot as “steadfast love,” “mercy,” or “devotion,” which deepens our understanding of this psalm. Just as revealing is the Hebrew l’olam or “forever,” because it can mean limitless space—the universe—as well as limitless time—eternity. To put it into simple language, we might say “His chesed is always there!”

This is our response through an account of the creation:

Who alone does great wonders

Who by understanding made the heavens

Who spread out the earth on the waters

His chesed is always there!

His chesed is always there!

His chesed is always there!

But then we come to a line that I always found jarring: “Who struck Egypt through their firstborn . . . His chesed is always there!” If you miss my point, the language gets more violent later on:

Who struck down great kings

And killed famous kings

Sihon, king of the Amorites

And Og, king of Bashan

His chesed is always there!

His chesed is always there!

His chesed is always there!

His chesed is always there!

How exactly is striking down the firstborn of Egypt or the great kings Sihon and Og an act of chesed—lovingkindness? These acts might be necessary, and might ultimately bring about a loving result for humankind as a whole, but they still seem like an odd way to illustrate God’s ever-present chesed. I’m sure we can find some great answers to this question in the traditional commentaries, but I’ll suggest one answer that applies particularly to the middah of lovingkindness.

No matter what the circumstances are, God’s chesed is always there. It isn’t shaken or compromised by the stubbornness of Pharaoh or the idolatry of Sihon and Og. God doesn’t get rattled by events, but always responds in chesed, whether or not we understand it as such. Likewise, the chesed we need to practice must be steady and unshakable. It doesn’t turn off and on according to the behavior of those around us. As I noted when we covered chesed in our last cycle of middot, Messiah gave us a similar instruction:

“But I say to you, love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who spitefully use you and persecute you, that you may be sons of your Father in heaven. . . . For if you love those who love you, what reward have you?” (Matt 5:44–46)

I also suggested an exercise to help us learn chesed. Since I’m still working on that, I could use a review of the exercise, and you probably could too, so here it is: Seek an opportunity each day to 1) do an act of kindness, 2) for which you’re unlikely to be recognized or rewarded, 3) on behalf of someone who doesn’t even appear to deserve it. Try it when you’re driving. Let the road hog have your lane on the freeway, and bless him as he squeezes in. Give a buck and a big smile to the panhandler on the off ramp. Or later this week, invite the bore or the complainer at Oneg Shabbat to sit at your table.

Such chesed reflects the character of Hashem, whose chesed is always there, even for the undeserving—since no one actually deserves it anyway. If Hashem can put up with us and show us chesed, how much more should we show chesed each day to a fellow human being, whether we consider him deserving or not!