When we realize that “love your neighbor as yourself” is part of the great commandment of the Shema (Mt. 22:37–40; Lk. 10:25–28), it increases our responsibility level substantially. A Torah expert talking with Messiah Yeshua realizes this increased responsibility and seeks to limit it with a question: “And who exactly is my neighbor?”

Yeshua’s response, the tale of the so-called “Good Samaritan” (Lk. 10:30–37), makes it clear that “neighbor” includes anyone we might run into who has need of our neighborliness. Or, to put it in the terms of an older tale—Cain and Abel (Gen. 4:1–15)—the answer to “Am I my brother’s keeper?” is “Yes, you are, and you might be surprised at who turns out to be your brother!”

So, as we are working on the middah of responsibility, we learn that we are responsible for others as well as ourselves. Is there any limit to such responsibility? Let me suggest a couple of limits, not to discourage the practice of responsibility for our neighbor, but to make it sustainable in the real world.

First, we need to maintain responsibility for ourselves as well as for our neighbors. This is the oxygen-mask principle. You remember; when your flight is about to take off, the attendant tells you that, in the unlikely event of the cabin losing its pressure, an oxygen mask will drop. If you’re traveling with a small child or someone else in need of assistance, put on your mask first and then help the other person. Why? Because if you try to help them first you might black out from lack of oxygen and be of no use to anyone. Hillel’s famous statement is similar; “If I am not for myself, who will be?” So, the answer to the question, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” is “Yes, and you’re your own keeper too.”

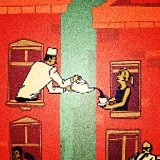

Second, you generally don’t want to take more responsibility for the other than he is willing to take for himself. I say “generally,” because sometimes we have to help someone who can’t take any responsibility at all, like the poor beaten-up stranger rescued by the Samaritan. The Samaritan takes him to an inn, covers his expenses, and offers to pay for more upon his return. I’d imagine, though, that if the Samaritan returns and finds the man fully recovered and healthy, he’ll expect him to start covering his own room and board. In fact, at some point it doesn’t help a person at all to take too much responsibility. This is the plow-horse principle. Yes, I actually plowed behind a horse in my early days, and I was amazed at how hard it was, especially when I’d finished a small patch and looked at the huge field that still needed turning. But then someone told me that I wasn’t supposed to push the plow, but let the horse pull it. My job was just to keep the horse moving in the right direction—much easier! As long as the horse felt me pushing, he went slower and slower so he didn’t have to pull. Some people are like that; if you take too much responsibility for them, they won’t take any for themselves. So, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” “Yes, and he’s his own keeper too.”

The third answer to “Am I my brother’s keeper?” is a bit different—“Yes, but Hashem is the ultimate keeper.” You are responsible for your neighbor, but ultimately God alone is responsible for every life. This truth has two implications: First, don’t start taking responsibility for your neighbor’s inner workings. Love your neighbor as yourself, but don’t try to change her, don’t start thinking you know best what she really needs because you love her so much. There’s a realm of the other person that belongs only to God. Second, even when you take responsibility for your neighbor in the right way, and with the right limits, you sometimes fail, or your neighbor sometimes fails. We have to leave the outcome to Hashem.

So, the answer to Cain’s sarcastic question is yes, you are your brother’s keeper, but Hashem is the keeper of us all.