When I began to focus intently on the Shema earlier this year, I realized I’d have to make some changes to line up with what I was reading, three in particular: I’d have to really practice loving Hashem my God with all my heart, with all my soul, and with all my might. I’d have to start binding “these words” on my hand and forehead in the form of tefillin (more about that in a moment), and I’d have to recite the Shema morning and evening.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s not like I was neglecting these things altogether, but I just wasn’t practicing them with enough intensity. I was reciting the Shema every morning, or just about, but rarely in the evening, even though it seemed clear enough in Scripture. So I turned to the “The Bedtime Shema” in my siddur, which includes a prayer ending, “Blessed are You, Hashem, Who illuminates the entire world with His glory.” Then you recite the Shema, just Deuteronomy 6:4–9, followed by “May the pleasantness of my Lord, our God, be upon us—may He establish our handiwork for us; our handiwork may He establish.” Amen, and then off to sleep.

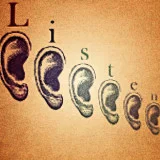

Notice that this simple ritual takes the words of the Shema literally: “you shall talk of them . . . when you lie down, and when you rise up” (Deut. 6:7). You can argue that this isn’t meant literally, that it might just mean speaking of Scripture all the time, not literally reciting the specific words of this paragraph when you lie down every night and rise up every day. But the literal application brings a certain order to my day. Whatever else happens, not matter how crazy or chaotic it might get, my day is bookended by the Shema in the morning and the Shema before I drift off to sleep.

In a similar way the instruction to bind tefillin in the next verse—“You shall bind them as a sign on your hand, and they shall be as frontlets between your eyes”—might have been originally intended as figurative language. Back in Exodus 13, when Moses gives the law of redemption of the first-born, he says, “It shall be as a sign on your hand and as frontlets between your eyes . . .” clearly a figure of speech here, as the same terminology is in Proverbs 3:3, 6:31, and 7:3. I remember reading somewhere that Rabbenu Tam, grandson of Rashi, who wrote the definitive tract on binding tefillin, also believed that the language was metaphorical, but applied it literally anyway. The language might be figurative, but if there’s a way to fulfill it literally, all the better!

The point is simple enough—sometimes the way to inner, spiritual order is through outward order. Sure, you can keep your desk tidy and your email inbox up-to-date and still be a mess inside, or you can be a mess outside and in good shape within, but the particular genius of Jewish spirituality is to embrace both inner and outer. It often gets at the inner through the outer, the spiritual through the literal. So, as it says,

Happy are we, how good is our portion,

how lovely our fate, how beautiful our heritage.

Happy are we who, early and late,

evening and morning,

say twice each day –

Listen, Israel: The Lord is our God, the Lord is One. (Koren Siddur)